SO-2: Surprising Results as We Begin

The Science: Observation, #2. Setting an Initial Hypothesis and Collecting Our First Data Points

We began this series in the last chapter, SO-1: The Crucial Role of Observation, by establishing our initial map of the territory we wish to observe: a strong relationship of equivalence between each unique feeling state and an equally unique and corresponding configuration of virtual material properties.

FeelingA ☰ VM-propertiesA

We continued by establishing several key factors which provide confidence that our observations of the virtual material properties associated with a unique feeling state will be captured accurately and consistently.

Now that we have established this starting map, we are ready to move forward with our observations.

Narrowing Down Our Territory

Our opportunity is to begin observing the virtual material properties of specifically named feeling states. But the realm of feeling is huge. It might be helpful to narrow down the territory we seek to observe.

Perhaps we could choose to zoom in on a specific type of feeling experience. Because we have no idea what we will find, we’re probably better off starting with a very simple framework, one that’s been around a long time. Something like Ekman’s six basic emotions may fit our needs: happiness, sadness, anger, fear, surprise and disgust. Ekman’s theory held that people everywhere experience these basic emotions in the same way, and that, for example, we naturally “read” the emotions in others through their facial expressions, regardless of cultural influences.

Let’s move forward with that basic idea. We’ll pick one of these six that seems like it might be easy to investigate: sadness.

Starting with a Hypothesis About Sadness

If we begin with Ekman’s theory, our hypothesis will hold that all people experience sadness in a similar way. Perhaps we add further resolution by looking at some existing evidence that might point to exactly how people experience sadness and give us some direction in proposing what the virtual material properties might be. Let us draw upon the following two sources in constructing this aspect of our hypothesis.

First, we might look through common language. People often use metaphorical terms to describe the experience of emotion, and the emotion of sadness comes with many that are very common. Here are a few:

Heavy – “A heavy heart” / “Weighed down by sadness”

Broken – “A broken heart”

Dark – “A dark mood” / “Dark thoughts”

Aching – “An aching sadness”

Drowning – “Drowning in sorrow”

Waves – “Waves of sorrow”

Sinking – “A sinking feeling”

Hollow – “An empty, hollow ache”

Cold – “A cold loneliness”

Foggy – “A fog of sadness”

Lost – “Feeling lost in sadness”

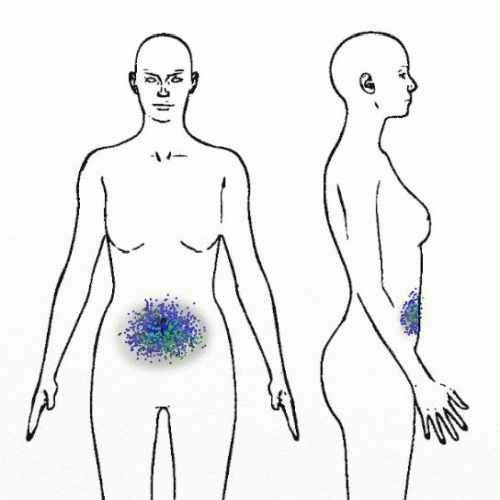

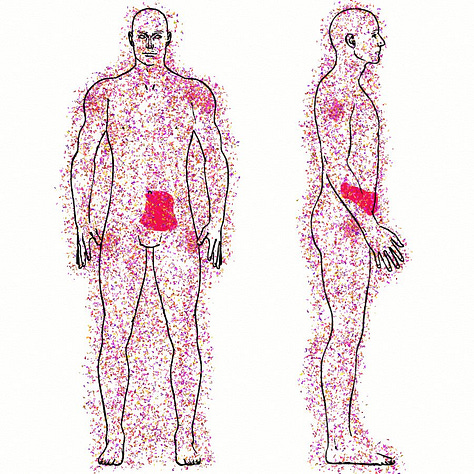

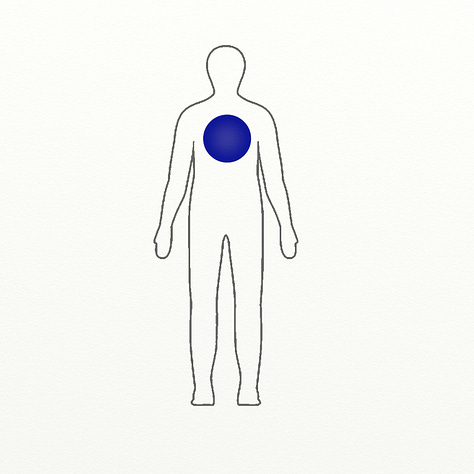

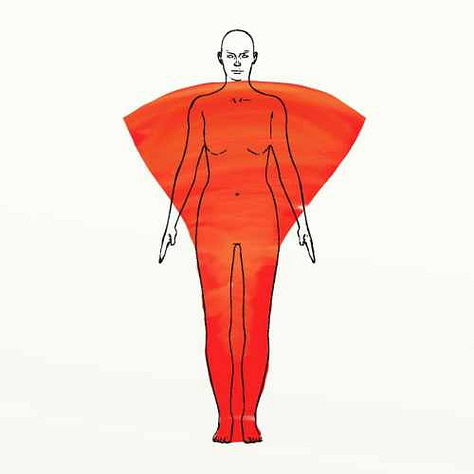

Second, we might look to some research in cognitive science explorations of the sadness experience. One study offered a dramatic visual presentation in 2013. As reported in Bodily maps of emotions, by Lauri Nummenmaa et al,[1] the researchers cued hundreds of subjects to access emotional experiences like happiness, sadness, anger, and others. To do so, they provided simple words, stories, movie clips, and facial expressions, and invited people to draw on an outline of a body to indicate places where they experienced increased versus decreased body activation. The results of this data were compiled into images like this comparison between Happiness and Sadness, where warmer yellows and reds (brighter) indicate increasing activation and cooler blues (darker) indicate decreasing activation.

Pulling this all together, we might say that we expect the virtual material experience of sadness to have the following characteristics:

Located primarily in the chest, and secondarily in the throat and eyes, with a general deactivation in most of the body.

Generally heavy, dark, and with a downward directionality to it, possibly with components of pain, emptiness, fog or disorientation.

Further, touching back to Ekman’s theory, we can say that while we expect some variability from one person to another, we expect a clearly discernible similarity in the configurations of virtual material properties that show up for different people mapping a feeling they each have named Sadness. We can add this to the components of our starting hypothesis:

The experience of sadness should be similar among different people.

What do you think? Is this a reasonable place to start?

Beginning to Observe Sadness

In what follows, I will be offering a few examples from many years of mapping with myself and others (all identifying information has been removed). These examples are representative of what you will find if/when you decide to map similar feeling states.

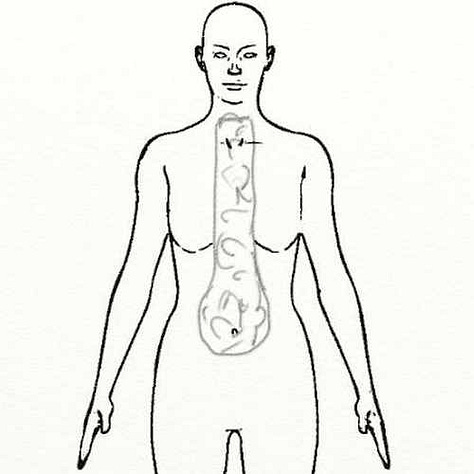

Sadness #1

A kind of blue, maybe bluish green, dark thing in the pit of my stomach. A sense of resignation associated with it. Like a little doughy, glowing thing. It just sort of sits there and feels sad. Cold. It has inertia, so if I move around it sort of sloughs around. Sound of a sigh, with a half-sob, my voice.

For some reason I associate it with looking off to the side. Like it’s trying to find a way to not be itself, but it can’t, but it still looks. “Well, that’s that. This pretty much sucks.” It can even verge into despair and desolation, getting heavier and darker.

Sadness #2

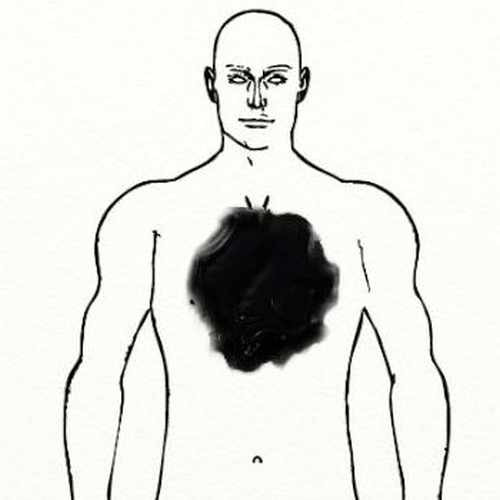

In my heart. Intense heaviness, crushing inward like a black hole, about the size of a ball of pie crust, could mold it with two hands. Black, outer surface is indented as if molded by hand. A very dense clay, oily, like plasticine but pitch black. Intense cold. <Sobbing.> Much bigger, actually, like a basketball, extremely dense, extremely cold, intensely black as if you are peering into the maw of infinite sorrow. No sound. Steady gravity.

About all the pain — my parents’ & others’ as well as my own. There is too much pain, too much fear, too much grief, too much loss, too much devastation. Too much for any human to bear. I cannot bear it.

The first example seems to be somewhat in alignment with our expectations, although it’s definitely lower in the body than we might have expected. The second one also seems fairly consistent with our expectations. Both share a coldness and a doughy substance quality, but how do we make sense of the difference in location?

One curious question that might arise at this early stage: Is it possible that gender plays a role in our feeling experience? Might men tend to experience sadness in their chest and women in their lower abdomen? What other factors might explain this difference that has shown up between these two examples? One way to start answering questions like these: collect more observations!

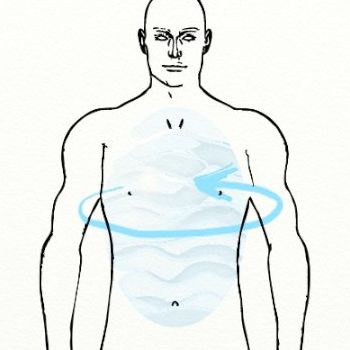

Sadness #3

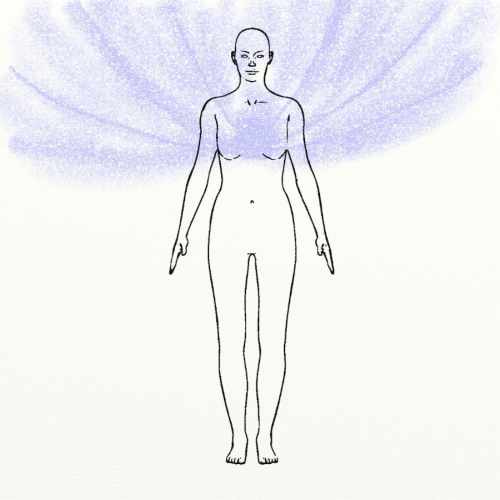

Coming from outside, energy folding in around my heart, coming around my whole head and upper body, coming from outside and coming to just exist inside me. Energy; neutral temp; white and blue and gray, transparent, wispy; a feeling of resignation, it comes in from the outside and folds in, from all sides. Sound of a sigh, my voice.

It’s a feeling of futility, spent energy, can’t sustain itself. It all comes collapsing back in. I have always had this incredible awareness of how finite life is. Not a fear of dying young, but even if I live for 90 or 100 years, it will end. This futility of existence.

OK, well, that was not what we were expecting, was it?

So Much for Our Hypothesis

With these three simple observations, we have shattered our hypothesis about the experience of sadness being similar among different people.

Not only that, but we also seem to have shattered our hypothesis about what virtual material properties correspond to the felt experience of sadness, and where they are likely to be located. The location can be in the chest, yes, but it can just as easily be found in the lower belly, or even outside the body! The color can be dark, yes, but it can also be “white and blue and gray, transparent.” And the substance can be heavy, yes, but it can also be “wispy.”

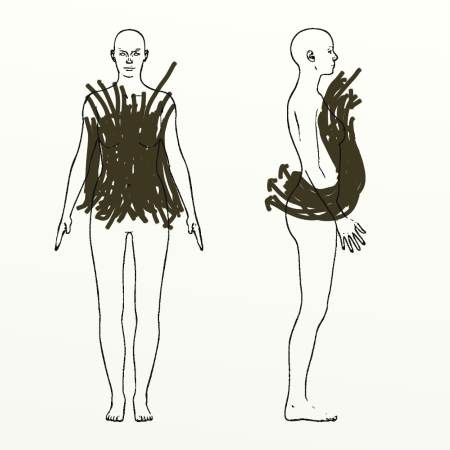

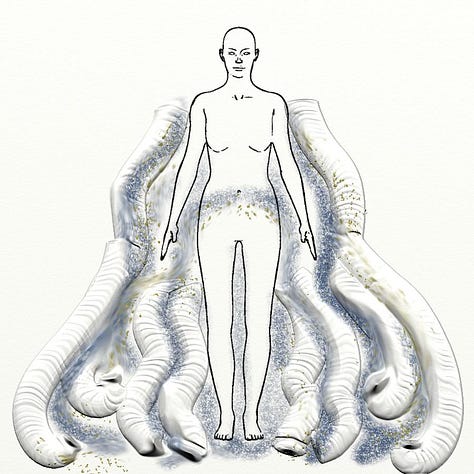

Of course, we’re only working with n = 3, so you might think we’re getting ahead of ourselves. So, just for the fun of it, let me toss in a few more drawings of Sadness to show you a wider spectrum of the diversity we find.

We have all sorts of configurations of virtual material properties here, all of which were named by the people experiencing them as Sadness. The one above on the bottom right is bright red, and its substance is rising. “Really?” you might wonder, “Sadness can be red? And moving upward?” Yes. And it can be hot. And substances can range from solid, liquid and gas all the way through to pure emptiness.

Oh my. This truly is astonishing, yes? I remember in the first months of leading other people through observing their own feeling states being completely flabbergasted at what showed up in other people. “You mean, your experience of sadness (anger, joy, fear, etc.) is 100% different from mine??” One thing this does very quickly is send you hurling towards that radical curiosity I talked about in chapter IS-10. We really have no idea what to expect, so it’s best to leave expectations at the door.

What We Are Left With

What do we do with this? At the moment, we have been sent scurrying back to square one. To move forward, it might be helpful to try to recast our hypothesis, to anticipate a different kind of pattern than the one we were expecting to find.

How about this as a new hypothesis that is consistent with our observations so far: Every person has a unique experience of what sadness is for them. For Jared, sadness corresponds to one virtual material property configuration, while Jamilla’s sadness is a very different configuration. And Jessica’s is yet another.

In our next chapter, we’ll take a look at how well this hypothesis holds up. Do individuals perhaps each have a unique “sadness signature”?

And again, a point of curiosity: If this is the case, might similarities or differences between feeling state signatures play a role in the “vibe” two people experience in relating? It’s an interesting question, eh? One that should send us scurrying toward more observations!

[1] https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1321664111