OK: a bit of a summary of what we’ve got so far before I turn you loose to do some fieldwork.

Over the previous chapters here in this section, I’ve laid out a few basic ideas for how a new science of subjective experience might be founded. Above all, I established that we need an adequate method for more reliably observing subjective experience in ways that enable more consistent comparison between one person and another despite the subjectivity barrier and the limitations of language.

Then I delivered the basics of fieldwork, a method that seems to fit our needs by enabling us to observe previously-unacknowledged virtual material properties of the feeling experience. But at this early stage in our investigation into the nature of conscious experience, there remains much that is shrouded in mystery. For our science to progress in a way that might reveal patterns that reflect our inner reality and offer themselves as valuable components of our maps of that inner reality, we need to take things slowly. Let’s take a closer look at what we’ve got and how we should best proceed.

What We Have

As I mentioned above, our primary asset at this point is our method of fieldwork. We have discovered that if we turn our attention toward the inner experience of feeling and ask very specific questions comparing our experience to that of materiality, we get very precise answers. (See IS-8: A New Method for Observing Inner Experience.) These answers about spatial location, substance, temperature, color and other properties result in a detailed, tangible and unique snapshot of each feeling experience.

Our second asset moving forward is that we experience this snapshot as having some form of validity, especially confirmed in its capacity to serve as an interface by which we are able to interact with the feeling experience directly. By deliberately altering the virtual material properties of our snapshot, our feeling experience simultaneously shifts. This asset of direct engagement gives us the ability to verify our observations (see the “slider test” in FM-11: Pro Tips), a fantastically useful ability as we move forward with our science. It also enables us to intervene in our territory, to “experiment,” pushing on A to see what happens to B, to further multiply the power of our observations and our accompanying capacity for pattern discernment.

These two assets open a very large door to investigation. Perhaps it is a little too large in some ways. Because of this, moving forward, I am going to lead us in choosing to focus on our baseline asset, the mapping experience, to find out what we can learn if we restrict our activity to its capacity for observation alone. We will apply the second capacity to interact with the feeling experience using the virtual material interface only as a way of validating our observations. If we move a property and experience a shift in feeling, we have established that we have captured something essential about the feeling experience itself.

My intention in doing this is to help us avoid going too fast, getting out of balance and falling over into ungrounded theorizing and speculation. For now, we will minimize our use of the capacity for interaction. One small step at a time will be our best way forward.

Now that we’ve established our stance in moving forward, let us acknowledge a few more advantages that come with our new observation method.

The First Advantage: Virtual Materiality

Earlier, I discussed the limitations of our vocabulary for emotions like sadness to carry definitive comparisons from one person to the next. To be clear, it is also true that we cannot know, for example when someone perceives the substance of their sadness as solid, that the experience is the same as that of someone else who also assigns the substance of solid to their sadness. Nevertheless, we are able to shorten the correlation chain significantly by staying within the realm of subjective experience as it interfaces with the more consistent domain of more objective properties of the material world. The experience of materiality is a universal constant among living beings.

To take “solid” a little further as an illustration, we can say the following, building on the fact that the materiality of our bodies is similar enough, person to person, to make some generalizations:

None of us can walk through walls. When we press against a solid, we experience our body being effectively resisted by that solid.

None of us is immune to the effects of gravity. When we lift a heavy solid, we experience a greater force of its weight bearing down toward the center of the earth than when we lift a relatively lighter solid.

Our bodies have their own solidity. When we grip a ball of clay, we experience our fingers pressing into this softer, yielding solid.

All of us have a measure of tactile sensitivity. When we run our fingers over a lump of pumice stone, we experience something very different from holding a billiard ball.

We also experience the capacity to perceive temperature through our skin. Picking up a warm cup of coffee generates a somewhat universally different experience from holding a snowball.

Drawing from these generalizations, we can say with some assurance that when one person describes their feeling state as being a hard, rough, heavy, cold solid, that their experience carries a relatively high correlation with the experience of someone else describing their experience with the same properties. Of course, when our inner perception of virtual material properties strays into less physically common territory like “energy” and “light” substances, we may lose some of that strong correlation between our reports and our more universally shared physical experiences. Nevertheless, we have gained a significant shortening of the correlative chains by linking our feeling experience to that of the material world.

The Second Advantage: High Resolution Perception

In addition, the increased resolution of our observational data provides an opportunity for far greater possibilities to identify patterns shared among people. To clarify what I mean by this greater resolution, here is a list of variations of terms for various experience of sadness, providing a more fine-grained vocabulary advocated by researchers like Lisa Feldman-Barrett.

Melancholy

Sorrow

Heartache

Despair

Grief

Dismay

Longing

Aloneness

Homesickness

Forsakenness

Mourning

Fragility

Ache

Resignation

Yearning

Nostalgia

Regret

Bittersweetness

Disenchantment

Disappointment

Languishing

Dejection

Hopelessness

Despondency

Anguish

Malaise

Void

Heaviness

Tragic Awe

Existential Gloom

Rejection

Alienation

Embarrassment

Inadequacy

This is useful, of course. Expanding from a single term, sadness, to a few dozen provides us with a more nuanced vocabulary by which to match a word with our experience. This helps us make better sense of our own experience as well as providing more effective paths for communicating our experience to someone else.

At the same time, we are still bound by the limitations of language and the subjectivity barrier. We have no idea whether my experience of a feeling I have named “rejection” matches your experience to which you have given the same name. No idea. Something about the social context and the general flavor matches well enough for us to have the experience that we understand one another when we use that word to describe our experience. But in the context of a science, the experience itself remains impenetrably vague.

Let’s compare this to the following fieldwork description of one person’s experience of what they have called “sorrow.” Here we have a more specific name for the sadness in the word “sorrow.” But on its own, what does that tell us about the person’s lived experience of being the one who is experiencing that sorrow?

One Person’s Experience of Sorrow

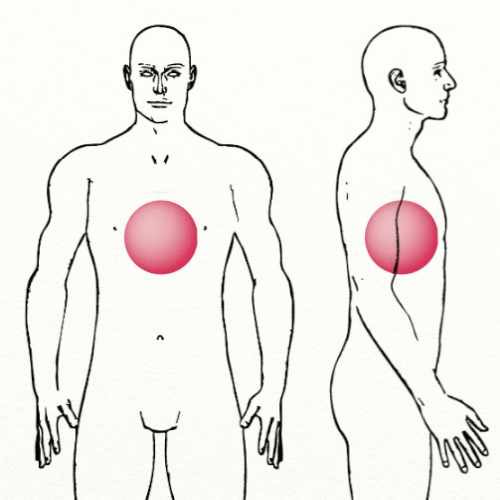

Solid, soft ball, size of a large grapefruit, texture of rose petal, heavy, pendulous like a water balloon, moist, feverishly hot, deep red. Sound is a deep, throbbing hum. There's some power in it that stabilizes things. The hum is a vibration of an energy in and through it. The energy may extend out beyond the ball.

Looking at the description of the observations of virtual material properties, however, we can see a massive leap forward in what we are able to perceive about the actual inner feeling experience. Let’s look at a few qualities to see what the possible “range of motion” might be in the expressiveness they offer.

Temperature — a linear spectrum from infinitely hot to infinitely cold. Too many perceptual possibilities to count.

Location, size and shape — pretty much infinite in what might be possible.

Substance, color/appearance, movement, sound — again, all of these offer virtually infinite realms of possible values for the property.

Put all of these together and we gain literally an infinite realm of possible observational specificity. The two approaches cannot be compared.

You might have the reflection that, if we talk with this person about their experience of their sorrow, there would be very much more information we could gain about that experience. Well, we don’t lose that opportunity by mapping the experience’s virtual material properties. Here is how this sorrow was described:

We broke up. I long for her love. I grieve its loss. I believe I will never have the love I want. I am not safe. Safety is necessary for love. I am fed. That is ok, but my deeper needs are not met.

What this more story-based description gives us is a way to connect our own experience of sorrow or sadness with this person’s by triangulating our stories. We can remember a time when we lost a relationship and imagine into this person’s experience through our own memory. But what we’re establishing here is that without mapping our own story-connected experience, we don’t know at all whether the two of us actually experience sorrow in the same way.

And a Couple More

The experience of fieldwork feels both novel and familiar. The novelty comes in translating feeling experience into a highly detailed description built from the proto-language of virtual materiality. While this overlap has shown up in limited contexts, it remains an unfamiliar way to conceptualize what we feel.

This novelty makes it less likely we'll be swept into collective, shared meaning-making. It enables the explorer to simply report observations without fitting them into existing categories. Describing frustration as having qualities of a dark, hot solid that vibrates with high tension seems just as valid as describing it as a vividly glowing liquid sloshing in a pit. Compared with a statement like, “We broke up,” there are no value judgments attached, no interpretations, no imposition of societal norms. The data is relatively free of cultural obfuscation.

Additionally, feeling experience itself tends to remain relatively stable as we engage with it, much more so than the swiftly-transforming features of thought. When we name a feeling state, we identify something with persistent existence. Often, a state we explore has been a familiar occupant of our interior life for years, if not decades. When we bring our awareness to it for mapping, it tends to hold still as we examine it.

Not only does it remain stationary during observation, but we can often return to it hours, days, or months later and find the same properties in place. This consistency offers a much more stable terrain for mapping and trusting our maps.

An Appropriate Tentativeness

To give ourselves a sense of what this new capacity for high-resolution observation offers us, let us consider what it would be like if our earth’s atmosphere was perpetually shrouded in a thick cloud cover. Let’s place ourselves a few hundred years ago, before our technology gave us the ability to fly. We would have light in the daytime, and darkness at night, but we would have no access to seeing the sun or moon or stars. In our earlier history, our theories about what brings day and night would be quite crude.

For example, perhaps the mythology of light and dark might center on the idea that the earth beneath our feet “breathes.” At night, the earth inhales, breathing in the light and sending our world into darkness. In the daytime, the earth exhales, sending light out into the clouds above to illuminate our daily activities.

Then imagine we discover a mountain range that enables us to climb above the cloud cover. Immediately, we would be able to see an unprecedented level of detail that would provide giant-step insights into the nature of our daily cycles. In our first step above the clouds, we would be dazzled by a new reality. Our first impulse, perhaps, would be to explain the sun as being “coughed up” or “spit out” in the morning by the clouds below it, and then swallowed again as night falls.

But we would be best served by patience, taking our time to observe the daily rhythms from this new perspective. Eventually, we might recast our story, taking into consideration our new awareness of these bodies of light — sun, moon and stars, which travel from one horizon to the other. Eventually, using our new capacity for high-resolution observation, we would have the opportunity to travel a journey of discovery leading to our current understanding of our planet orbiting the sun and rotating on its axis as the explanation for our daily cycles.

In the same way, we want to apply caution and patience as we move forward here, taking our time to make these new observations, giving ourselves the space to notice fresh patterns and avoid imposing the old patterns on this new information. We discerned the old patterns, and built the stories around those patterns, from a meager supply of vague observations. It is time to release our perceived patterns and our stories about them. It is time to enter this new investigation with a fresh and radical curiosity about what we might discover.

What We Need, Moving Forward

We’re entering unmapped territory here, a true frontier in our human exploration of reality. The territory we’re exploring is internal, off limits to our customary methods of observing and navigating the material world. At the same time, this territory is the closest of any to what it is to be human. It is an essential space for us to explore if we are to truly master our lives here together on this planet.

In entering such a sacred and virgin territory as this, we must proceed with humility. Whether the explorer is ourselves or someone we’re facilitating, we must enter in the spirit of service.

Our situation is different from previous episodes in which we have entered new geographic territories to explore. Then, many things remained the same. Water still flowed from high places to low, plants still grew where water was plentiful, wildlife still lived where plants grew lush, and the same general principles and needs for safety and sustenance applied, no matter what landscape we might have traversed.

In our new inner frontier, we cannot be confident that anything we previously have learned will apply here. We simply do not know what to expect.

Our tool, fieldwork mapping, enables us to enter this previously inaccessible space and bring vivid awareness to its shapes and features. Our goal must simply be to support the explorer in using this tool to observe and create maps of their own private inner terrain. In every session, we must bring respect and humility, enfolded in this attitude of service.

Moving forward, how will our investigation best be served as we enter this unknown realm? These are my suggestions to those of you choosing to join this endeavor of building a new, first-person science of subjective experience.

Take things slowly. In order to make our observations, we must navigate our territory. But we have no maps by which to confidently navigate. So we must go slowly and carefully, prioritizing small steps, harvesting our learning with each step, attempting to make our first rough maps and testing them as we go.

Cultivate curiosity and openness. The bottom line is, we do not know what to expect. Consequently, we serve our investigation best by expecting to be surprised. If we conduct our investigation as a solo explorer, we carry a curiosity about what we might discover. If we facilitate someone else’s exploration, we support them by welcoming whatever shows up.

Maintain steadiness and consistency. Our prime asset is a method for observation. It has been developed sufficiently enough to provide a thorough scaffolding for collecting high-quality observational data. We will serve ourselves by relying on the structure of the process to carry us, and we will serve the process by executing it steadily and consistently, going through the same process with each new observation.

Optimize thoroughness in collecting data. We are looking for patterns by which to make sense of this new territory. But we do not know, yet, which information will best serve us in discerning the most relevant and useful new patterns. Because of this, our investigation is best served by thoroughness. We take detailed notes of our observations.

Avoid imposing existing frames. It is entirely possible that our observations may confirm an existing map of inner territory. But it is also possible that what emerges requires a wholesale revision of all existing maps. We simply do not know. Consequently, at the beginning, we must proceed as if we know absolutely nothing beyond the raw data of our observations, and let the patterns emerge from that data and nowhere else.

Shed the materialist scientific frame. Our goal in this science of subjective experience is to map the territory of our actual, conscious, lived inner worlds. When coming from materialist sciences, we might want to jump right into making universal maps. We might assume, for example, that virtual material properties for sadness can be analyzed statistically to find out its universal substance, temperature and color. It will be important to drop this impulse until we find out more about what we’re observing.

Honor subjective experience. We want to avoid allowing existing concepts to shape perceptions and interpretations. Our observations should be as pure as possible, carrying an absolute beginner's mind into this new territory. We don't know what we'll observe each time we enter, and we want our observational data to be as faithful as possible to the inner experiences we're observing.

Most importantly, within ourselves and with everyone for whom we facilitate fieldwork, we must enter the space of observation with respect for whatever shows up. We affirm its existence, confirm our observation of it, and support it in fully entering into awareness. In doing so, we honor subjective experience as the frontier of reality we have chosen to enter.

Our Long-Term Intention

Entering an unknown frontier is a long-standing human practice. We enter new territory and produce maps to help navigate it. To produce a map, we make copious observations and discern patterns that form entities and relationships, noting the larger context within which these hold steady. When done well, these become integrated into a reliable, consistent, useful map, and our frontier gradually transitions into the familiar. We master the frontier.

That's what we're up to here. Over time, as we accumulate observational data from many individual, personalized maps of inner realities, we will begin to notice connecting patterns that help us make sense of the universal features of this inner realm.

What turns out to be most important in the emergence of these new, more universal maps will be a new distinction in what we observe. Traditional approaches have focused on collecting information about experience's contents: What is the person seeing or hearing? What are they thinking? What memory is being called to mind?

Our new approach prioritizes structure rather than contents. For now, we'll avoid over-interpreting what we observe. We're going to take our time. Eventually, we'll begin to notice patterns we could never have expected. These patterns will reveal a previously hidden structure to conscious experience, an underlying, universal architecture.

That's all I can say for now. Just know that we're embarking on an extraordinary journey. To get started, we must absolutely let go of our expectations and bring our full presence and commitment to investigating the actual, lived experience of feeling deep within ourselves.

This is a lot. And it is new and fresh. We have an opportunity before us to make genuine new discoveries. Standing at this frontier, do you feel both the uncertainty and the excitement? We do not know, and we can discover.

For those of us whose nature is one that resonates with the essence of science, this is exactly where we want to be. This is exactly what we were born to do. For us, nothing is more satisfying than to step into a new frontier such as this.

Perhaps check in with yourself right now. What are you feeling as you read this? Give that feeling a name and consider taking it through the fieldwork process in the next section to learn more about this part of yourself.