How Discoveries Are Made

Learning from the Story of the Interstitium — a New Organ in Your Body

Science progresses only as fast as the threshold of observation. We can theorize up and down the wazoo, but until we find a way to observe what our theories say exists, we cannot depend on that portion of the theory-map for reliable navigation. Because of this, most everyday science tends to confine itself within the bounds of our technologies of observation. Which is fine. There’s plenty to do in that very-big space.

So what happens when we devise a new way to conduct our observations? A great example came in the last decade with the invention of fluorescence endoscopy. An endoscope is a microscope placed at the end of a long tube and inserted into the body to observe tissues in the digestive tract and other places. This invention added the ability to deliver special molecules that glowed under specific frequencies of light to highlight cellular and other microscopic structures, along with the ability to shine that calibrated light and examine the tissues under great magnification. All of this can now be done in living tissue, inside a living person.

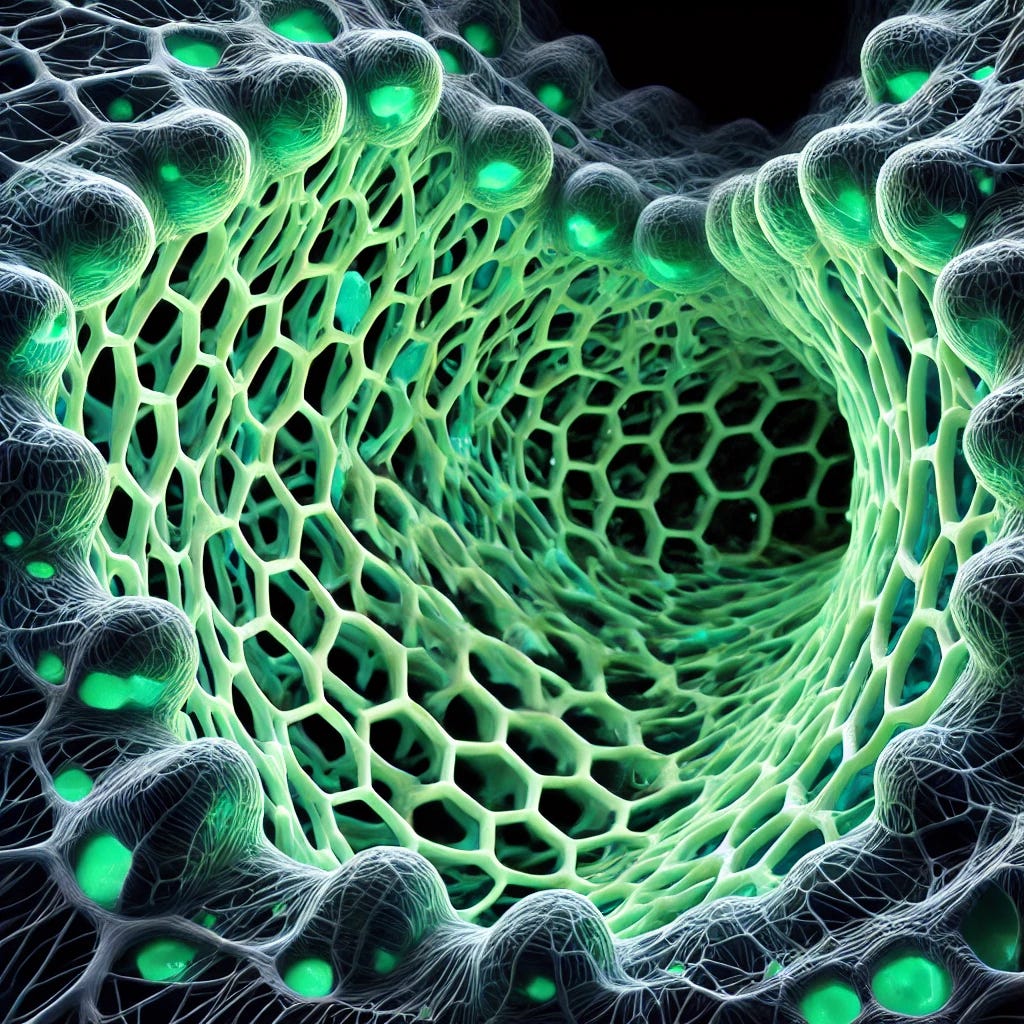

Using this new observational tool, Dr. David Carr-Locke was examining a patient’s bile duct and was mystified by what he observed. The duct wall looked like a honeycomb, with chambers of glowing fluid throughout. He had never encountered such a structure, either in practice or in school, and rushed some photos to consult with his friend Dr. Neil Theise, an eminent liver pathologist.

Theise had no idea what he was looking at. In pathology, you’re studying the structure of dead parts of the body. He had looked at countless bile duct walls over his career, and they had all looked pretty solid, just a wall of collagen fibers, nothing interesting about it at all. Yes, there were cracks throughout the wall, but everyone had just assumed those cracks were an artifact of heating and drying the sample to prepare it for the microscope. This fluid-filled honeycomb structure had never been seen before.

Over the next few days, Theise realized that these cracks in collagen wall pathology samples were present in all kinds of tissue all throughout the body. He wondered whether the cracks were actually the collapsed honeycomb chambers, all dried out like a compressed sponge. He went back to Carr-Locke and convinced him to look at some other living tissues, volunteering himself for examination.

The first thing they looked at was his skin. He injected some flourescein, ran the scope over his skin, and damn if it wasn’t glowing with honeycomb chambers of fluid. What was this?? And what did it mean?

Theise had a friend, Dr. Becky Wells, who worked with a fancy imaging device that could take flat slides and assemble them into 3D images. He paid her a visit, and what they found was that these honeycomb structures were actually assembled into networks of tubes through the collagen tissue.

This was getting really interesting. Nothing like this had ever been described in the history of western biological science (although it is very present in Chinese medicine).

Well, over the past few years, a lot has been learned about this new “organ” in the body. It’s called the interstitium, and it circulates four to five times more fluid through the body than the blood traveling through the circulatory system. Its functions are complex and multifaceted, affecting nearly all the systems of the body in ways previously unknown, and touching on pretty much the entire edifice of medical knowledge.

All of this from a new method that enabled us to observe something previously invisible to us.

(My description of the discovery of the interstitium comes with gratitude from the work of Jennifer Brandel, in her article in Orion Magazine and her RadioLab episode. Also see a summary in The Daily Beast and the original Nature article.)

Keys to Discovery

The story of the interstitium provides a great illustration of the general patterns of discovery. We can learn from this example what to look for as we take our first steps into the murky realm of inner experience. First, though, we should probably ask, What exactly is discovery? What are we examining here?

Reaching back to our earlier discussions, Maps Within Maps and Building Good Maps, we can easily define discovery as follows:

Discovery: Identification of stable patterns of observed experience that enable the construction of new entities and relationships in our operational maps of a given territory, leading to more effective and reliable navigation of that territory.

With that, let’s look at the necessary steps for constructing useful new map components.

1. We reliably and methodically observe something we haven’t seen before.

Discovery depends upon new observation. We may gain a new capacity for observing some existing territory or apply an existing method of observation to a new territory. Or we may acquire both at the same time, a new capacity for observing and a new territory to observe.

Not only that, but we must be able to apply this observational method reliably and methodically so that we can be sure that Observation #1 can easily be compared and contrasted with Observation #2 without needing to compensate for differences in the observation process itself. Further, we must be able to make many observations, and through our many observations we must be able to glean patterns from our observational data.

In the discovery of the interstitium, endoscopy was already an established tool, easy to reliably and methodically use. The flourescein dye was also able to be applied reliably and safely. So it was relatively straightforward to use the new tool combination to make many observations and accumulate enough observational data to discern patterns.

2. We make sense of our observations.

The key requirement for new observations to carry the potential for discovery is that our new observational data cannot be interpreted using our existing maps. It doesn’t make sense, given what we already know. In the discovery of the interstitium, honeycomb fluid chambers were showing up in connective tissue all through the body, and we had no idea what they were. We needed to make sense of what we were observing.

2a. We identify new, stable patterns of observational data and begin to construct new entity and relationship components for our map(s) of the territory.

Right from the first observations using this new flourescein endoscopy, the interstitium researchers could see there was something new. They ran their observational method over and over again to confirm that yes, in the place where previously we had only seen dense, opaque walls of collagen were open fluid passages. They were able to confirm that this pattern showed up in many different types of tissue, in many parts of the body.

2b. We find ways to interface our new map components with existing maps.

Upon seeing the images of the honeycomb structure in the wall of the bile duct, Neil Theise became obsessed with its incongruence with existing knowledge and determined to make sense of it. He leapt back to his long history examining bile ducts and all manner of other connective tissue barriers through the body and noticed a possible connection with the ubiquitous cracks in these collagen walls. Were these not cracks, but collapsed fluid chambers? This spurred further investigation.

In this way, throughout science, a new discovery involves cycles of curiosity-driven inquiry:

Old open questions that yield to this new discovery (e.g. how cells and molecules travel between organs or from one part of the body to another)

New questions that shed new light on old map components (e.g. The gross patterns of interconnection among these fluid passages)

Placing the discovery within or at the edge of an existing map, or proposing an entirely new territory (e.g. reinterpreting what had previously been understood as dense collagen walls, well within the existing anatomical map but at the edge of certain maps of functional physiology)

Correlation with previously observed but possibly misinterpreted data (e.g. the cracks previously interpreted as caused by desiccation)

3. We triangulate our observations with other observational methods to enhance our understanding.

Many times, a new observational method and the new patterns that emerge raise new questions. Often, these questions present opportunities to other, previously existing methods, inviting a triangulation between the new and alternative methods to learn more about what has been revealed.

With the discovery of the interstitium, Theise’s reaching out to Dr. Wells to create a 3D model of a series of microscopic images was such an example. In another example, the researchers stretched their capacity to observe living tissue by freezing biopsies after delivering the flourescein, then being able to much more thoroughly slice through larger volumes of tissue and reconstruct 3D models of what they found.

Other methods used in researching the interstitium include tracking things like tattoo ink, colloidal silver, and hyaluronic acid as it travels from its point of origin across tissues and organs into the system at large. In this way, the more extensive interconnectivity of the interstitium as a body-wide fluid migration system is being mapped out. (See this article in Nature.)

4. We triangulate our observations with other observers examining similar territory using the same or similar methods.

In scientific research of all kinds, we employ something called replication to confirm our observational data. Another scientist or team uses the documentation of the observation method to set up their own observation of a similar territory. Similar results confirm the original data while different results either call the original into question or expand it in new directions.

Sometimes replication is done by duplicating the original study, and in other cases the methodology or focus is modified somewhat in order to explore a nuance or edge case with the intention of collecting more robust sets of data. By triangulating in this way, we strengthen our capacity to build more universally reliable and effective maps. Over recent years, this has been done with the research upon the interstitium, strengthening the original discovery and expanding its reach.

5. We engage in a wider-reaching inquiry to strengthen, challenge, and refine our new map components.

Once we have established that there is indeed a “something” — some previously unidentified entity or relationship within our territory of interest, no matter how poorly defined or understood — the real work begins. Again, as scientists our overriding intention is to construct reliable, universally-applicable maps for navigating some portion of the territory of life’s experience. It’s all about the map.

5a. We find new questions arising, and new answers to old questions.

One of the most compelling aspects of entering discovery territory is the way the world shifts and expands. When we discover something that doesn’t fit, we naturally face a wide array of possibilities.

What is this “something”? Is it one thing, or more than one? What are its boundaries and what defines those?

What relationships does this “something” hold with other portions of my existing maps? With other things co-arising with this one?

How does the existence, or potential existence, of this new “something” influence or change the existing entities and relationships of my existing maps? Have I misunderstood something? Are there new insights emerging?

One of the most important practices in this weaving the new tapestry of entities and relationships is that we hold our interpretations loosely and find ways to productively explore our questions and answers. When we enter a new territory, or see something new in a familiar territory, we enter the unknown. It is most essential that we hold that attitude of not knowing, of supreme curiosity, of respect for the ultimate mystery of existence.

5b. We engage the territory of our new map.

The whole point of a map is to enable navigation. Navigation involves not just passively moving through an unchanging territory, but engaging with that territory to produce desired changes. The full “territory” includes not just the entities and relationships (and ourselves) in their current state, but all states possible for this arrangement to become.

For example, in the developing map of the interstitium, we have an abiding interest in learning how to interact with this new “organ” to produce desired changes that can protect from disease and support health. This is where the ubiquitous scientific practice of the “experiment” comes in.

In general, an experiment is very simple. We have a working map of the territory, and this map suggests that pushing on part A should cause some change in part B. But we’ve never actually seen this happen. So we set up two conditions:

Condition One (control): We do nothing and observe the changes in part B.

Condition Two (experiment): We push on Part A and observe the changes in part B.

In this way, we find ways to strategically interact with perceived entities and relationships in the territory represented by our evolving map. We’re looking to learn more about the territory itself and its relationship to our map. We want opportunities to build and strengthen new entities and relationships to better represent that territory and enable more effective navigation through its potential state space.

5c. We challenge the new (and old) components of our map. Where does our model break down?

All the while, as we build new map components to incorporate our new data, we have an inherent investment in finding ways to stress test those models. Where does the model break down?

Remember, our overriding goal is to produce universally relevant and reliable maps by which to navigate a territory. We seek to create maps that others can trust. If someone uses the map, and the results they get differ from what the map predicts, that’s a problem.

So we try to reduce the likelihood of those failures by actively seeking ways to break the map ourselves. We look carefully to find weaknesses, or potential weaknesses in the existing map structure. Then we design ways to push the envelope, actively engaging the territory in these regions in ways that could yield results contrary to the map’s predictions.

In the interstitium research, right from the beginning the researchers broke old map predictions. The old map held that pancreatic connective tissue walls were dense and solid. By freezing living tissue after treating with flourescein, then examining under a microscope, that old map shattered.

That’s what we’re looking to do in any science that pushes into new territory. And that is what psychotopology has done, as you will see.

6. We go back to the beginning and start all over again.

When we break the components of our map by demonstrating that the map’s predictions do not hold under experimental conditions, we gain a liberation from the old way of seeing things. This liberation invites a rethinking and a redesign. How else can we assemble the sum total of our perceived stable patterns into entities and relationships that better serve our navigation through the territory? This opportunity comes whether we have broken an existing, long-standing map or one that’s been freshly proposed and not yet tested.

Honestly, this is where the rubber meets the road in science. This is where the scientist is served by having as little investment as possible in a current set of maps, and as much inner freedom as possible to tolerate the discomfort of the unknown mystery of being.

Applying This to a Science of Inner Conscious Experience

So, here we are. Standing on the precipice, looking into the mystery. We’re not talking about studying something new in the body. Not considering how to research a new chemical process. Not contemplating moving forward with investigating the functionality of light waves or universal background radiation.

Sophisticated technology won’t help us here, at least not at the beginning. How do we apply these six discovery keys to the study of inner conscious experience? Is it even possible?

Laying out these six keys to discovery does help us. But our moving forward depends on our developing a method of observation that actually can serve this approach. Namely, it has to make visible something previously invisible, be able to be applied methodically, and yield perceivable patterns that suggest new entities and relationships. Just to get started.

This exploration of discovery makes it clear why existing efforts have not yielded a proper science of inner experience. It all depends on the observation, and because of the subjectivity barrier we have not had an adequate method for that.

This is where psychotopology changes the game. In the next post, I will introduce our new method for observing inner experience with precision, reliability, and discipline. And once we have that in place… well, you’ll just have to wait and see for yourself.

The Promise of This New Science

To a committed scientist, facing evidence of something that has no referent in current maps is one of life’s most exciting moments. In my own life, this process of discovery feeds me more than anything else, and I have sacrificed a great deal of life’s normal pleasures in service to my research.

I’ll be doing my best to retrace my route for you in coming posts as together we build this new science of inner experience. Several key breakthroughs serve as mileposts for the journey, each of them applying the keys to discovery I’ve outlined above. I’m looking forward to laying it all out for you and giving you everything you need to recreate the discovery path for yourself.

Are you ready to step into your new role as a first-person scientist of subjective experience? Let’s go!

Subscribe?

If this intrigues you and you want to learn more, I recommend you subscribe. There’s a lot to look forward to, and subscribing will keep you in the loop.

If you would like to be more involved than just reading and commenting, consider a paid subscription at $9/month or $90/year (with the option to sign up for the Esteemed Supporter level with a higher annual contribution). For paid subscribers, I host a more active Engage community where we will have periodic live calls and chats, providing richer opportunities to connect.

A bonus for paid subscribers in these early days: In the live calls, you will have an opportunity to experience and learn about fieldwork before the full series of posts is published here, so you’ll get a jump on things. Plus, becoming one of the first subscribers will give you this special access in a super-small group.

I also invite you to reach out to me by email if you have bigger questions: put the “@” between “frontiers” and “psychotopology.com” in the Frontiers of Psychotopology URL.

Reflections

Here’s your chance to influence how I move forward by adding your reflections in the comments below.

How does this post land for you?

What in you feels like it is being spoken to in this post?

What questions are you left with? What are you most curious about?

What feedback would you like to offer me, in service to my being able to share this new work with you and the world?

What feedback could you offer toward improving my writing of this post?

Comments are open to all, and I do hope you will consider also subscribing so we can stay in the loop with one another as this evolves.

Thank you.

Thank you for being here, thank you for reading, and thank you for sharing your thoughts in the comments below. I look forward to meeting you soon.

One last note. I’d love for you to thoughtfully spread the word about Frontiers of Psychotopology. For example, reach out to someone you think would appreciate this, and tell them why. Alternatively, here on Substack, feel free to share with your beloved subscribers.

The discovery of the interstitium overlaps with the meridian theory of Chinese medicine with an amazing overlap. And, just like interstitium break down as soon as one apply traditional anatomical method, meridian and qi can not be approached by standard, reductionist-based scientific method.

@Veronika Bond restacked this post with a provocative question: "If the landscape is different from the way you believed and were taught, would you rather learn about a new map, or insist on the old one which no longer serves us because it doesn’t represent the landscape?"

I replied with some reflections on what "serves" us, depending on the person and the context. Check it out and chime in with your thoughts: https://substack.com/@veronikabond/note/c-69967014